If you count profile alone, Landa was the star of drupa. Surely never before has a brand new, unproven printing process attracted so much attention. There were posters all around the massive Messe fairground, constant crowds on the stand looking at the prototype presses, and the five-daily presentations in the 380 seat theatre were booked up three days in advance.

Not bad for something you won’t be able to buy for a couple of years and which even its founder Benny Landa admits needs a lot of improvement before it’s ready for the market.

Mr Landa’s claim is that the Nanographic process that underpins the presses will revolutionise print. He says it will achieve the lowest cost per copy of any digital process, competing with litho costs for medium runs of 5000 to 10,000 copies, with the ability to print on standard offset papers as well as plastics, at high speeds. Quality claims are high too: super-sharp image dots; a wider gamut than CMYK offset; and an ultra-thin ink film that matches the underlying substrate gloss.

If Landa can deliver all that, printers will be falling over themselves to buy it. Indeed, the company was taking 10,000 Euro deposits for ‘Letters of Intent’ at the show, that gave them a preliminary specification and cost per copy, plus a priority place on the waiting list. It took twice as many as it expected, one of which was from 1st Byte in London (see the separate story).

‘Digital is today responsible for only 2% of all the pages printed worldwide’ Mr Landa claims. ‘We’ve only nibbled around the edges. To break through into the wider industry we’ve got to be able to match the quality, speed and costs of conventional offset, on all paper stocks. Ten years after founding Landa, we’ve set up new processes to go after the other 98%.’

On show were prototype web and sheet fed Landa presses in a range of sizes. All were unique in appearance, largely due to the huge black touch screen control panels that covered the whole of the operator sides. That they looked like giant iPads was entirely intentional. That part however, was just the icing on the cake.

The sheet fed models are the B3 format S5 (for 11,000 sheets per hour simplex, 5500 duplex), B2 (8800 to 12,000 sph simplex, 4400 to 6000 duplex S7 and B1 S7 (6500 to 13,000 simplex, 3,250 to 6500 duplex), taking paper from 60 to 350 g/m2. The S7 will be offered in configurations for either commercial print or folding packaging.

Landa S5

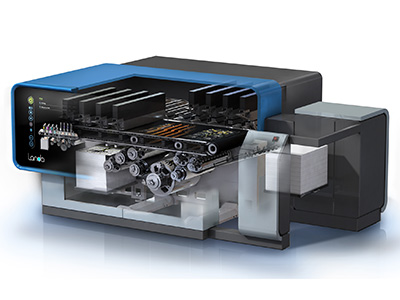

Landa S7 cutaway

The web presses are the 560 mm web width W5, for 100 to 200 metres per minute simplex; the 1020 mm web W10 running at the same speed; and the 560 mm W50 for up to 200 metres per minute duplex.

Landa W5

Landa W50 cutaway

Prices are loosely predicted to range from $1 to $3 million, call it £650,000 to £2 million. If this comes to pass, those prices will be at the low end of the scale compared to

equivalent inkjets, but the Landa presses will be faster and cheaper to run.

The industry interest is hardly surprising. Mr Landa has revolutionised print once before. He originally founded the pioneering digital printing systems maker Indigo and launched it to a surprised world at Ipex 1993.

Eight years later he sold Indigo to HP for a reported $800 million, since when he’s been ploughing a fair bit back in his home country of Israel, backing startup companies,

charitable endeavours and his own Landa Labs research and development operation.

The labs have been developing ‘alternative energy technology,’ as well as ‘nano-materials’ for drug delivery, personal care products, composite materials and the pigments that go into the Nanographic process.

Mr Landa was famous for his drupa and Ipex presentations at Indigo. For his new company he managed to go even further over the top, with a 40 minute show including modern dancers, pounding music and Mr Landa appearing miraculously in a spotlight to treat the audience to his vision of the future.

However, there was substance backing the showmanship. In the weeks running up to the drupa Landa announced that it had licensed its technology to two of the world’s biggest offset press makers, Komori (which supplied the running gear for the Landa presses at drupa) and Heidelberg. As the show opened manroland sheetfed also signed up.

So, looking past the dry ice and the dancers, how does Nanography work? In a nutshell, it’s an offset inkjet , though the company doesn’t put it that way. It’s based around a new NanoInk that uses minute particles described as ‘a few tens of nanometres across.’ A nanometre is a billionth of a metre.

These particles comprise pigments coated with a polymer resin that Mr Landa describes as ‘a hot melt adhesive.’ They are suspended in water which acts a vehicle to deliver them to the print heads. Although Landa insists on calling its heads ‘ejectors,’ it also says they are based on standard Kyocera KJ4 piezo inkjets. The difference hasn’t been explained. Mr Landa says that other heads can be adapted as faster models are developed.

What also makes Nanography unique is the way it works inside the press. Instead of jetting the NanoInk pigment particles and water straight onto the substrate like normal inkjets, they are sprayed onto a heated moving blanket belt. This passes under all the colour heads, building up the image. After the image is built up, the blanket travels a further distance to allow the heat to evaporate the thin film of water, leaving just the resin coated pigment particles which in turn partly melt to become sticky.

The blanket is then brought into contact with the cool paper or plastic substrate, held on an impression cylinder. The resin particles immediately solidify and adhere to the substrate, peeling completely off the blanket to leave it clean. The clean area of the blanket belt continues back around under the ejectors for the next image to be built up. The benefit of the heated blanket and sticky resin, says Landa, is that it’s essentially a dry process at the point of transfer.

The biggest limitation on ‘conventional’ aqueous inkjet press speeds is drying the ink, plus finding a paper coating that doesn’t absorb too much or too little water while it does so. Nanographic printed sheets are dry immediately, so they’re ready for duplex printing and then downstream finishing processes as soon as they hit the delivery.

No water on the paper also means that virtually any material can be used, with no worries about special coatings. The ink bonds to the top layer of paper fibres without wicking very far into them, so the dots remain sharp and the colours are bright and consistent on most substrates.

Anyone familiar with the ElectroInk process used in HP Indigo presses will start to feel déjà vu at this point. ElectroInk uses an electrophotographic imaging process rather than inkjet ‘ejectors,’ but the heated blanket (a cylinder in this case) and peel-off ink film transfer onto cool substrate sounds very similar. Is the Landa process in reality an inkjet Indigo for the 21st century?

Well, up to a point. The nanometre scale pigment particles are all-new and have a revolutionary effect on image quality, Landa claims. They absorb a lot more light than conventional pigment particles, which makes them very powerful colorants with very good abrasion resistance. The ink film on the substrate is only 500 nm thick, so it takes on the same surface appearance.

Controls for the iPad generation

The touch panel shows interactive displays of the machine status, job lists, current job previews, and contextual touch controls. This is an entirely new way of controlling a press. Magnets are used to attach pull sheets from the press next to visual displays of the job images. If the press is left unattended, the display switches to large representations of a few critical functions that can be seen from a distance: paper, ink levels, job finished, and an unscheduled stop.

So how does it print?

So that’s the theory. The reality isn’t quite there yet. Landa wasn’t handing print

samples out, but it was displaying them behind Perspex, so you could see them up close.

Most samples, as seen above, showed a few stripes or bands due apparently to blocked jets, which should be curable. They also had small white spots in shadow areas, suggesting incomplete transfer of the ink from the belt. Clean transfer is vital, so the company will certainly be working hard to get it fixed.

‘We have to test, test, test,’ says Mr Landa. ‘We launched Indigo in 1993 and were overwhelmed with orders. So we built a factory and shipped it. We didn’t have the money to wait then. Now we can afford to wait to get it right, and then ship.’

At present, he said, the presses can’t handle variable data, though that will be available when they ship. The front ends appear to be based on Global Graphics’ Harlequin RIPs.

Landa’s three licensees seem likely to pursue different implementations of the process, though all have signed up for sheet fed and not web. Mr Landa says that manroland has only taken a license to sell Nanographic presses to its installed base, meaning it will not sell them to new users.

Landa’s main interest in Nanography is manufacturing and selling the NanoInk. ‘The question is whether as a single supplier you can guarantee good prices,’ Mr Landa admits. ‘The deal with the customer will be that these inks will make this the lowest cost per copy of any digital print process.’

The company will sell NanoInk to Landa press customers directly and also to its licensees (ie the three press makers and any others that sign up in future) so they can resell it to their customers. However, Landa will not sell ink to its licensees’ own customers, so there won’t be any issue of undercutting them on price, he said.

‘Printing has only declined by about 2% in the past five years, but capital purchases have halved. The market is afraid to buy new offset equipment in case it becomes obsolete. We say offset is not obsolete, that Nanography is complementary. It is a new order in the industry: the suppliers are having to say I would rather help my customers than hurt my competitors. This is the first time that all the main offset players have embraced the same digital technology.’