Deep sea water is slowly sucked into the seabed. But precisely where they are going, no one knows.

The ocean is not just what we see. In the deep sea there are still separate currents, even this can be considered a different form of “sea” from what is experienced on the water.

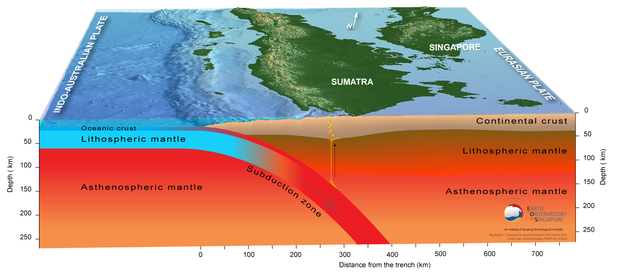

And while seawater slowly rises as the ice melts, the bottom water is actually absorbed at the same time. Where they sink is unclear, just know that this is the result of tectonic plate collisions. In other words, water is sucked into the ground, called a “subduction zone”.

Subduction is a geological concept that takes place at the converging boundaries of moving plates, in which one plate sinks under the other, creating an attractive effect.

Aspiration rates are measured at a few centimeters per year. However, according to a recent study, this water absorption rate is 3 times higher than what had been calculated by science before.

“People still know that subduction zones can absorb water, but it is not known how much water it is”, – said Chen Cai, author of a doctoral thesis at the University of Washington (St. Louis).

“But this research shows that subduction zones actually take up more water from the deepest layers of the Earth than we thought,” said Candace Major, director of the Ocean Science program at the National Science Foundation.

“The study results highlight the importance of subduction zones for ocean currents.”

The world is majestic under the ocean

To carry out this study, the experts spent more than a year “listening”. The sounds they heard were vibrations of earthquakes, tectonic plate collisions in the Mariana Basin (the world’s deepest ravine under the ocean). They use 19 seismic recorders in the region, as well as 7 recorders on the neighboring islands.

The Mariana Basin is also the boundary between the Pacific tectonic plate which slides over the Mariana Plate, forming a subduction zone.

Previous studies have shown that this area can hold water, but it is not known how much of it and how deep it can descend. In other words, the amount of water sucked, no one knows.

“The previous calculations were based on the data available – that is, only at a depth of 6.4 km under tectonic plates,” Cai said.

“The method cannot accurately tell the thickness of the matrix and its water absorption,”

“Our research attempts to solve this question. If the water goes deeper, they can stay there, or even lower.”

Data shows that the “watery” rock foundation of the Mariana Slit extends 36 km below the seabed – much deeper than you might think.

The bottom is right up

As for the Marianas Valley, the water sucked in was four times greater than what had been estimated previously. Researchers can also explore similar regions around the world here.

“If the other subduction zones have similar properties, that means the calculations can be up to 3 times different,” shared Douglas A. Wiens, thesis guidance professor for Cai.

However, this does not mean that the water levels on Earth will decrease. The water sucked in will rise and the sea level has remained stable. In other words, the amount of water falling into the subduction zone will be released at a certain time, but cannot be absorbed into the ground.

Scientists previously believed that most of the water going down the trench would come back as steam, as the active volcano is several hundred kilometers away. But through research, they realize that the amount of water that goes into the soil seems to be far more than the amount of water returned.

“The calculation of the amount of water entering and leaving by volcanic activity is really uncertain,” Wiens said. “Research will have to be reassessed.

This is actually a normal thing, as it is difficult to calculate the water cycle in the world to reach an exact threshold.

Recently, Professor Wiens also applied the same calculation of geological activity to the Mariana Trench, but off the coast of Alaska – also an area with a subduction zone.

“Is the amount of water absorbed in other subduction zones different or not, depending on the shape of the tectonic plates?” Wiens asks questions.

The research is published in the journal Nature